Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

A surge of miniature satellites promises deeper insights into the cosmic microwave background-and along the way they're picking up bits of Earthly data. As research networks in low Earth orbit expand, privacy advocates, technologists and policymakers are racing to build safeguards that protect digital rights without grounding scientific discovery.

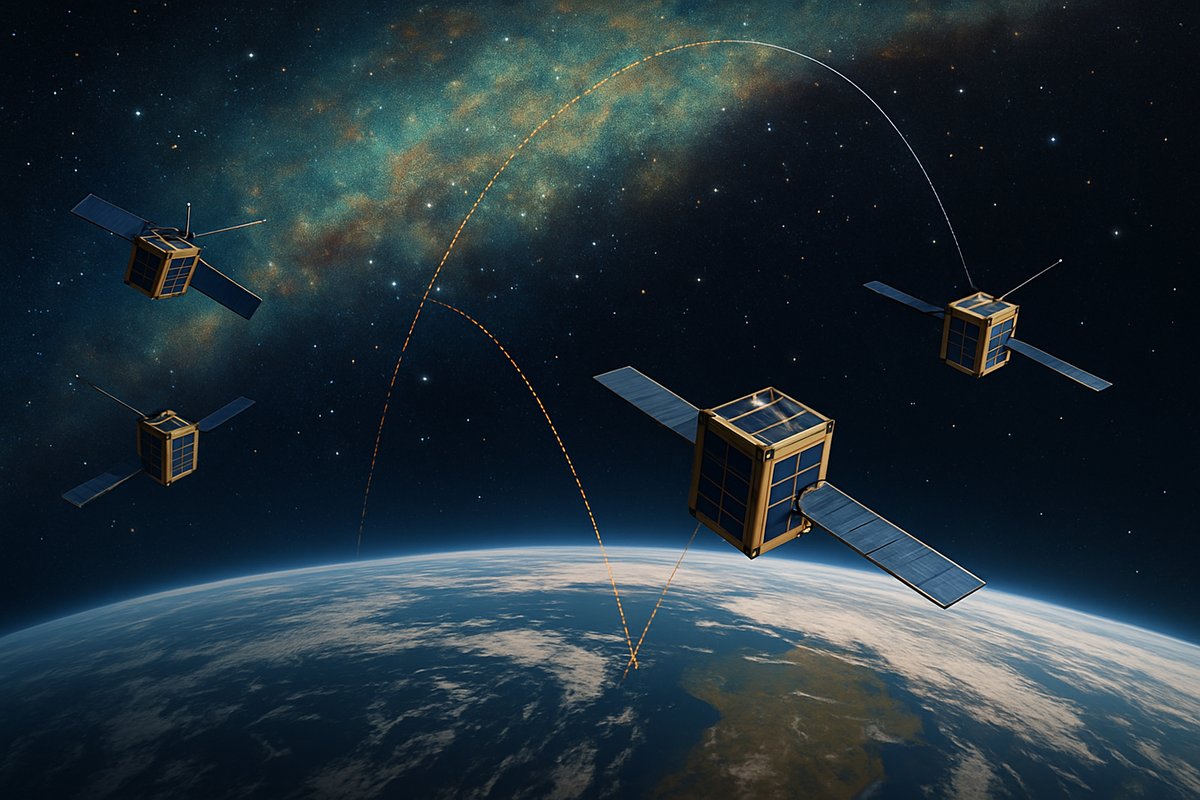

In recent months, a constellation of cube satellites designed to map the faint glow of the early universe reached full deployment in low Earth orbit. Each of these shoebox-sized spacecraft carries sensitive microwave sensors that sweep across the sky, searching for subtle fluctuations in cosmic background radiation. Scientists hope to use the new data to refine models of cosmic inflation, trace the distribution of dark matter and improve our understanding of gravitational waves traveling through space-time. Yet an unexpected side effect has emerged: these same sensors are inadvertently detecting signals from terrestrial networks-everything from unlicensed Wi-Fi beacons to encrypted messaging bursts-raising alarms about orbital surveillance, digital privacy and the need for ethical boundaries in space activity.

The root of the problem lies in the physics of antenna design. To register the feeblest cosmic microwaves, the satellites employ wide-angle receiving dishes with secondary lobes capable of picking up strong local sources of radio frequency energy. Even when pointed skyward, stray side-lobe reception can collect signals from ground-based transmitters, cellular towers and maritime data links. A recent technical report published by a consortium of university radio astronomers noted that nearly 45 percent of the raw data files contained ground-station interference above threshold levels. While engineers are working on digital subtraction techniques to isolate and remove Earthly noise from cosmological measurements, privacy experts point out that those same data streams could reveal patterns of human movement, network density and potentially intercepted communications traces.

Privacy and civil-liberties groups have rallied around the phenomenon, warning that unchecked space-based receivers may become the next frontier for mass surveillance. A policy think tank specializing in digital rights estimates that within two years more than 300 small satellites will be operating similar wide-field sensors. If left unregulated, those orbiting platforms could build detailed maps of population centers, infer user behaviors or even record metadata that intelligence agencies might exploit. Critics draw parallels to terrestrial surveillance cameras and spyware tools, arguing that satellites have the unique advantage of floating above national borders and legal jurisdictions while harvesting data in areas where regulatory oversight is still in its infancy.

Meanwhile, cybersecurity researchers are racing to develop portable detection devices and software toolkits that can identify when a terrestrial transmitter is being traced or profiled by an orbiting receiver. Borrowing methods from classical spyware-detection, these tools monitor signal patterns, track unusual downlink acknowledgments and alert network administrators to potential orbital “pingbacks.” Open-source projects have emerged with handheld radio frequency scanners capable of sweeping the local spectrum, flagging anomalies that suggest a satellite pass has collected-or attempted to collect-data from a given transmitter. In some urban test beds, participants have reported the ability to correlate scanner logs with publicly available satellite ephemeris data, effectively confirming that their home network traffic was scanned without consent.

On the legal front, lawmakers in several jurisdictions are taking notice. The European Union’s Digital Services Act has been interpreted by privacy advocates to apply extraterritorially to any system that processes citizen data, including space-based sensors. Similarly, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) establishes a framework for data minimization and user consent that could impose strict requirements on satellite operators collecting ground-originating signals. At the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, there is growing support for supplementing the 1967 Outer Space Treaty with guidelines addressing data protections, surveillance limits and the ethical use of remote sensing technologies. These evolving rules aim to ensure that scientific missions focused on cosmos and space-time research do not inadvertently cross into the domain of mass monitoring.

Ethical-tech initiatives have begun crafting on-board firmware upgrades designed to automatically filter out any signals that fall outside preauthorized cosmic frequency bands. By embedding frequency-masking protocols directly into satellite processors, operators can pledge to discard intercepted terrestrial traffic at the hardware level, eliminating any downstream risk of data misuse or retention. Proposals are also on the table for public transparency dashboards, where satellite owners would publish lists of actively monitored bands, operational timelines and sensor sensitivity thresholds. In parallel, a coalition of non-profits is developing an ethical accreditation program, akin to a “Fair Data Satellite” certification, to honor operators who adopt these privacy-first safeguards.

Scientific institutions are responding with a mixture of enthusiasm and caution. On one hand, the accelerating pace of satellite microfabrication and miniaturized sensing offers unparalleled resolution for mapping gravitational wave distortions, probing cosmic dawn phenomena and tracking dark-energy effects on large-scale cosmic structures. On the other hand, researchers acknowledge that public trust can evaporate if ethical missteps slide by unchallenged. As a result, some university mission teams have started partnering with digital rights organizations from project conception, embedding ethical oversight into mission charters, data-sharing policies and post-launch reviews. Collaborative working groups now include astrophysicists, signal-processing engineers, privacy lawyers and civil-society advocates, ensuring that both scientific and societal interests are represented in every design iteration.

The debate extends beyond professional circles into the realm of citizen science. Amateur radio astronomers and space-enthusiast clubs have begun calibrating their ground stations with a new focus on privacy protection. DIY radio telescope kits are being modified to include directional beam-blockers and custom-built faraday shielding, so hobbyists can enjoy studying the sky without fear of unintentionally collaborating in covert surveillance schemes. Workshops, webinars and maker-space meetups now feature joint modules on cosmic data analysis and personal data rights, creating a culture of informed participation in both observational science and digital-rights awareness.

Policymakers are also exploring market-based approaches to reinforce ethical norms in the commercial satellite sector. Insurance underwriters have started offering premium discounts to operators who commit to transparent data governance, while venture capital funds specializing in space technology have begun including privacy compliance metrics in their due diligence checklists. This financial incentive structure aims to nudge start-ups and established firms alike toward robust privacy-preserving designs, aligning investor interests with public well-being.

As these developments unfold, it is clear that the cosmic frontier and the privacy frontier are converging faster than anticipated. The next decade will likely see a proliferation of multi-purpose sensing networks-some devoted wholly to astrophysics, others to Earth observation, and many operating at the intersection of both. Establishing clear ethical guardrails now will enable the scientific community to harness the promise of space-time research, while safeguarding digital freedoms for individuals and nations alike. Without decisive action, the allure of advanced orbital technology risks overshadowing the very rights it should protect.

When the next generation of space explorers launches, they must carry with them not only telescopes and spectrometers but also a shared commitment to privacy, transparency and responsible innovation. By building ethical considerations directly into the hardware, software and legal agreements that govern these missions, we can ensure that the same sensors unlocking the universe’s secrets do not become unwitting tools of unwelcome surveillance. In this delicate balancing act-measuring fluctuations in the fabric of space-time while respecting the integrity of personal data-science and society stand to gain the most.

Only through collaboration among researchers, technologists, legal experts and citizens can we chart an ethical framework robust enough to guide the future of orbital sensing. The cosmos beckons with mysteries yet unsolved-and by designing surveillance-aware science from the ground up, we can answer that call without compromising the fundamental rights of life on Earth.