Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

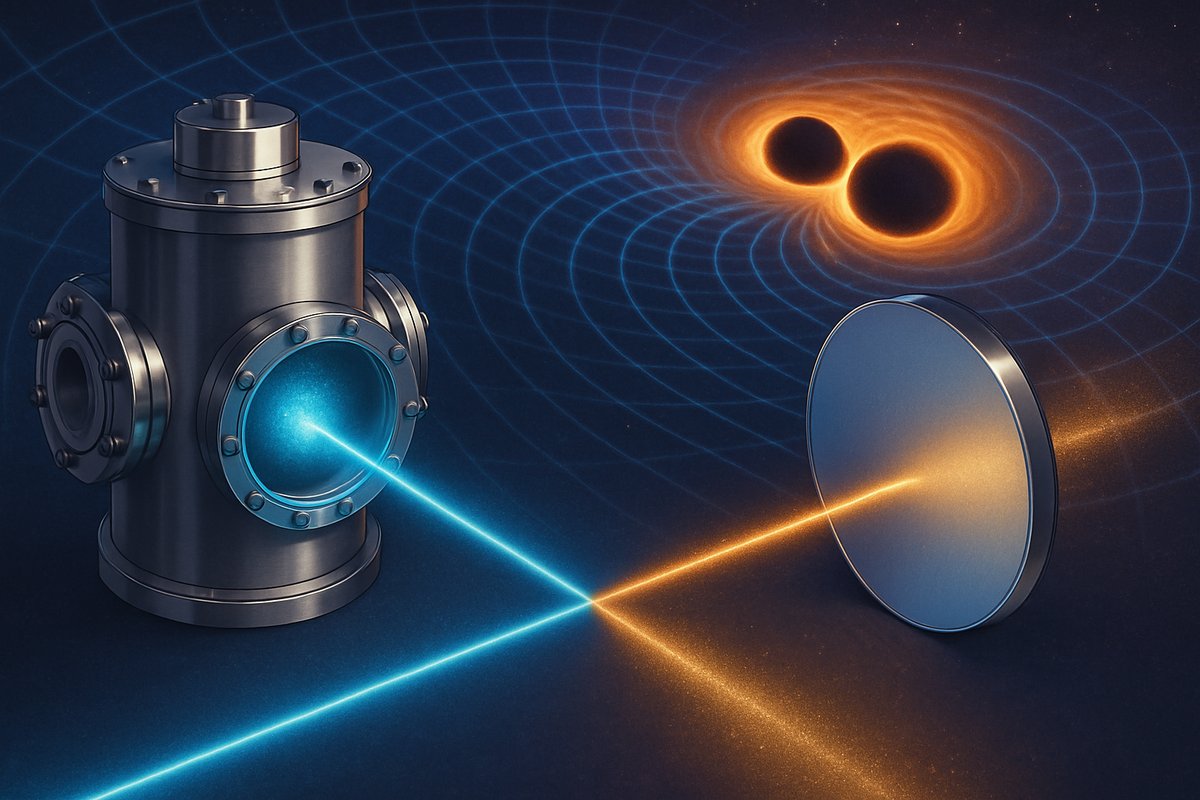

A new generation of quantum-metrology detectors is poised to open a mid-frequency window on gravitational waves, revealing collisions of intermediate-mass black holes and echoes from the universe's infancy. By merging cold-atom interferometry with squeezed-light techniques, researchers are advancing beyond traditional laser interferometers to capture cosmic ripples with unprecedented precision.

Gravitational wave astronomy has already rewritten our understanding of the universe, unveiling collisions of stellar-mass black holes and neutron stars. Yet today’s detectors, sprawling L-shaped laser interferometers spanning kilometers, remain blind to a crucial mid-frequency range where signals from intermediate-mass black holes and early cosmic processes should emerge. A wave of quantum-enhanced experiments-rooted in atomic interferometry and squeezed-light metrology-now promises to fill that gap, offering a richer symphony of cosmic vibrations.

At the forefront of this effort is a suite of cold-atom interferometer prototypes that use ultracold clouds of rubidium atoms as inertial test masses. In contrast to traditional mirrors suspended by seismic-isolation systems, these atom clouds follow freefall trajectories, sensing passing gravitational waves through minute phase shifts in matter waves. The UK’s AION collaboration and the US-based MAGIS-100 project have already demonstrated sub-picoradian sensitivity over hundreds of meters, a critical proof of concept for future observatories stretching from tens of meters underground to satellite baselines thousands of kilometers apart.

The core principle harnesses wave-particle duality. A sequence of laser pulses splits each atom cloud into two coherent paths, recombines them, and measures the resulting interference. A passing gravitational wave alters spacetime’s geometry, slightly changing the path length difference and thus the interference pattern. These shifts, imperceptible to classical sensors, emerge clearly with quantum-limited readout when squeezed states of light reduce quantum noise below the standard quantum limit.

Recent tests at Northwestern University’s cold-atom laboratory pushed phase-measurement precision beyond 10⁻¹⁴ radians. By injecting squeezed vacuum into the detection port and employing active stabilization of laser phase noise, researchers have cut measurement uncertainty by more than half compared to unsqueezed configurations. This breakthrough echoes the successful use of squeezed states in the Advanced LIGO observatories, which shaved down shot noise at high frequencies. Now, the same quantum tools are being adapted to atom interferometers targeting the mid-band between 0.1 and 10 hertz-a regime where planetary seismic noise is lower underground and astrophysical sources like intermediate-mass black hole mergers reside.

In September, a milestone came at the University of Birmingham’s 10-meter prototype, where a dual-species atom interferometer tracked both rubidium and potassium clouds. The differential measurement canceled common-mode noise, achieving strain sensitivity near 10⁻¹⁸ over a few seconds of integration. This platform laid the groundwork for AION-100, a planned 100-meter facility set to break ground next year. Coupled with plans for a companion detector in South Africa, the AION network aims to triangulate wavefronts and localize sources on the sky with arcminute accuracy.

Meanwhile, MAGIS-100 at Fermilab, leveraging existing tunnels, is upgrading to a multi-baseline design. By linking vertical and horizontal vacuum pipes, MAGIS-100 scientists will decouple seismic and gravitational gradient noise, isolating genuine gravitational wave signals. The US National Science Foundation recently announced funding to extend MAGIS to 500 meters, enabling sensitivity improvements that could detect early-universe stochastic backgrounds-relic ripples from phase transitions in the first seconds after the Big Bang.

Beyond terrestrial arrays, visionaries propose spaceborne atom interferometers. Deploying ultracold atom units on low-Earth-orbit satellites separated by thousands of kilometers would open a low-frequency window below 0.1 hertz. In this band, white-dwarf binaries and mergers of supermassive black holes whisper a cosmic bassline. By combining data from the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) and future quantum sensors, astronomers could trace gravitational wave spectra across ten orders of magnitude in frequency, testing General Relativity and searching for hints of new physics.

These quantum-enhanced facilities depend on ultra-stable lasers locked to high-finesse optical cavities, vibration-isolated platforms, and cryogenic vacuum chambers. Engineers collaborate with quantum optics experts to refine squeezed-light sources that maintain low loss over long optical paths. Recent advances in fiber-based frequency combs allow phase coherence to be transferred across kilometers of optical fiber, a necessity for multi-site synchronization.

On the theoretical front, astrophysicists are recalibrating event rate predictions. Models of intermediate-mass black hole formation-via runaway collisions in dense star clusters or direct collapse of massive gas clouds-suggest dozens of mergers per year within a few gigaparsecs. Detecting even a handful would illuminate how these elusive objects bridge the gap between stellar remnants and supermassive cores. Moreover, atom interferometers could detect chirps from exotic sources: boson clouds around black holes, cosmic string cusps, or ultralight dark matter fluctuations that modulate fundamental constants.

The integration of quantum metrology into gravitational wave detection exemplifies a broader trend in science: leveraging the counterintuitive properties of the quantum world to probe the grandest cosmic structures. From entanglement-enhanced imaging in biology to superconducting qubits for dark matter searches, quantum techniques are remapping the frontiers of observation. Here, at the intersection of quantum mechanics and relativistic gravity, researchers are designing experiments that double as technological testbeds, driving innovations in laser stabilization, vacuum engineering, and noise suppression.

Public engagement efforts are also ramping up. Data from prototype runs have been converted into sonified audio tracks, letting listeners hear the characteristic “chirps” and “rumbles” of passing waves. Educational outreach uses tabletop cold-atom demos to inspire high-school students, illustrating how wave interference can detect the faintest distortions in spacetime. Citizen science platforms are in planning stages, inviting enthusiasts to help sift through noisy data streams for transient signals-in the same spirit that volunteers contributed to early exoplanet hunting and gravitational wave confirmations.

The coming decade promises an orchestration of gravitational wave observatories spanning ground, underground, and orbit. Classical laser facilities like LIGO and Virgo will extend their reach with improved coatings and quantum upgrades. Mid-band atom interferometers will fill the frequency gap, while space interferometers survey the low-frequency realm. Together, this global network will capture a continuous record of gravitational vibrations-from the high-pitched chirps of neutron star collisions to the deep bass of cosmic mergers billions of years ago.

For researchers, the stakes are high. Observing the stochastic gravitational wave background could reveal the fingerprint of inflationary processes, unlocking clues about physics at energies beyond any terrestrial collider. Detecting signals from intermediate-mass black holes will refine models of galaxy formation and seed black holes in the early universe. And quantum-limited sensitivity may even uncover unexpected phenomena, offering a window into dark sectors or subtle deviations from Einstein’s equations.

As the first quantum-enhanced atom interferometers transition from prototypes to operational observatories, the dream of listening to the universe in all its frequency bands becomes real. Precision, awe, and curiosity converge in this next chapter of cosmological discovery, reminding us that the universe speaks in whispers-and we now have the quantum ears to hear.