Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

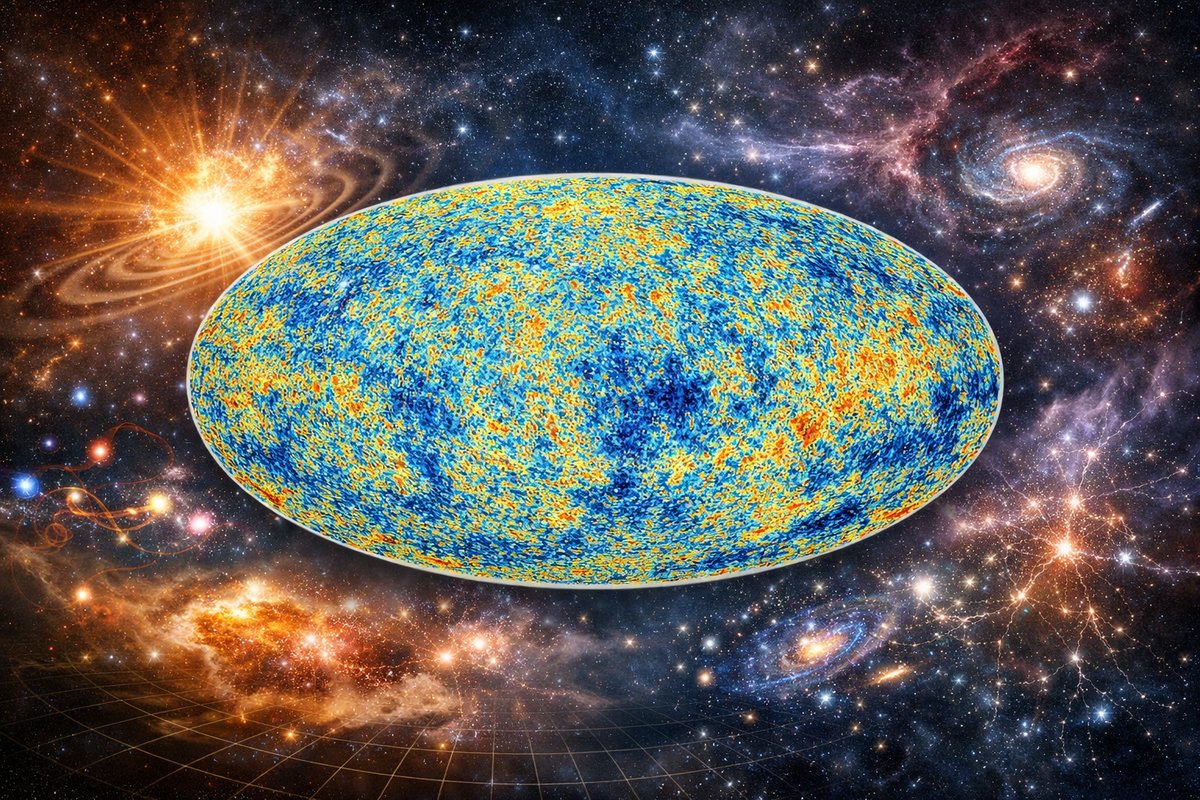

A new high-resolution map of the cosmic microwave background has revealed subtle ripples that carry the imprint of the universe's earliest forces. From inflationary surges to quantum seeds and lingering paradoxes, this investigation journeys through the stages that shaped all matter, energy, and structure we observe today.

An international collaboration of cosmologists and astronomers has released the most detailed polarization map of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) ever recorded. Collected by a high-altitude telescope array in the Andes, these observations trace minute fluctuations in temperature and polarization to better than one part in a million. Until now, the CMB-electromagnetic afterglow of the Big Bang-has stood as the most powerful snapshot of the universe when it was a mere 380,000 years old. The new map uncovers subtle twists known as B-mode patterns, signatures that could point to gravitational waves generated fractions of a second after the Big Bang. These faint distortions provide fresh clues about the nature of cosmic inflation and the exotic forces that dominated our infant cosmos.

The CMB has long served as a time capsule to the early universe. Roughly 13.8 billion years ago, as the universe cooled below 3,000 Kelvin, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen, allowing photons to travel freely for the first time. Those photons, stretched by cosmic expansion, now glow at microwave wavelengths. They encase an imprint of density variations seeded by quantum fluctuations during the inflationary epoch-an explosive growth spurt that enlarged tiny spacetime ripples by more than a trillion trillion times. The new data fill in missing contours of these primordial wrinkles, offering unprecedented resolution on scales small enough to test rival models of inflation.

Cosmic inflation remains a cornerstone of modern cosmology, resolving puzzles such as the horizon and flatness problems. The horizon problem asks why distant regions of the sky share nearly identical temperatures despite being causally disconnected. Inflation’s rapid expansion homogenizes all patches of early space, binding them within a common thermal bath. The flatness problem questions why the universe appears so spatially balanced, neither collapsing under its own gravity nor rushing apart too quickly. Inflation naturally drives any initial curvature toward flatness, much like stretching a rubber sheet. As researchers refine the shape of the CMB’s polarization, they edge closer to measuring the energy scale of inflation-potentially teasing out whether a single field drove the process or a cascade of interacting fields.

Beyond electromagnetic echoes, primordial gravitational waves remain the hottest target in early-universe research. These ripples in spacetime, predicted by general relativity, could have been generated by violent quantum fluctuations during inflation. Although direct detection from the early epoch remains elusive, instruments such as ground-based observatories and balloon-borne detectors continue to push sensitivity limits. Recent upper limits on tensor-to-scalar ratios constrain the amplitude of these waves to less than a few parts in ten trillion. Yet a confirmed detection would open a new window onto physics at energy scales far beyond the reach of terrestrial particle accelerators, potentially revealing the quantum nature of gravity itself.

While ordinary matter and radiation dominated the first few hundred thousand years, the invisible dark matter also played a silent but decisive role. Beyond the standard model of particle physics, dark matter remains a mystery, known only through its gravitational influence on galaxy formation and cosmic structure. Tiny density ripples in dark matter provided gravitational wells where baryonic matter could accumulate, eventually giving rise to stars and galaxies. Current experiments searching for weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), axions, and sterile neutrinos have yet to yield a definitive signal. Nevertheless, the new CMB data refine estimates of the dark matter density and its clustering properties, narrowing the parameter space for candidate particles and guiding future direct detection efforts.

Another relic from the early universe, the cosmic neutrino background, remains hidden from direct view. These nearly massless particles decoupled just one second after the Big Bang, streaming through space ever since. Though extraordinarily difficult to measure, their collective gravitational effect slightly alters the rate of cosmic expansion and the growth of structure. By combining the latest CMB maps with surveys of galaxy clustering, cosmologists now infer constraints on the sum of neutrino masses and the effective number of neutrino species. These findings intersect with laboratory results from neutrino oscillation experiments, stitching together a unified picture of how these ghostly particles influenced the cosmic tapestry.

Matter’s dominance over antimatter poses one of cosmology’s deepest paradoxes. According to known physics, the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of matter and antimatter, leading to mutual annihilation and a universe filled only with light. Yet our cosmos teems with matter, from interstellar gas clouds to living cells. This asymmetry hints at processes that violated charge-parity (CP) symmetry in the very early universe, possibly through mechanisms such as leptogenesis. High-precision measurements of particle decays in accelerator experiments complement cosmological observations, jointly probing whether the seeds of today’s matter imbalance were sown in the furnace of primordial interactions.

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) remains another cornerstone test of early-universe physics. Within the first few minutes, protons and neutrons fused to form light elements-primarily hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of deuterium and lithium. While observed abundances of helium and deuterium closely match theoretical predictions, the predicted amount of lithium-7 overshoots astronomical measurements by a factor of two to three. The so-called lithium problem has spurred proposals ranging from previously unknown particle decays to revised nuclear cross-sections. Resolving this discrepancy could unlock new physics beyond the standard cosmological model or refine our understanding of stellar processes that destroy surface lithium.

Speculative signatures of cosmic strings and other topological defects have also intrigued theorists. These one-dimensional filaments could arise during symmetry-breaking phase transitions in the early universe, much like cracks forming in a cooling crystal. Though searches in CMB data and gravitational wave observatories have yet to find definitive evidence, each new data release tightens constraints on the tension and density of such defects. If verified, cosmic strings would offer a direct glimpse into the high-energy field configurations that governed the young cosmos, opening a path to unify cosmology with theories of fundamental interactions.

Alternative scenarios to the standard inflationary picture continue to stir debate. Cyclic or bouncing cosmologies posit that our observable expansion was preceded by a contraction phase, potentially repeating through an endless loop of big bangs and big crunches. Other models invoke an ekpyrotic collision of higher-dimensional branes to explain the observed uniformity and flatness. While these ideas remain speculative, future observations of non-Gaussianities in the CMB or small-scale anisotropies could distinguish between rival paradigms, steering us toward a deeper understanding of the universe’s true origin story.

Looking forward, a new generation of telescopes and detectors promises to sharpen our view of the cosmos’s first moments. Space missions equipped with ultra-cold detectors aim to map CMB polarization over the entire sky with unprecedented clarity. Radio arrays will survey the redshifted 21-centimeter signal from neutral hydrogen during the cosmic dawn, tracing the birth of the first stars and galaxies. Proposed gravitational wave observatories in space will seek the long-sought background from inflationary ripples. Together, these probes form a multi-messenger approach to cosmology, leveraging light, gravitational waves, and particles to reconstruct the universe’s infancy.

From the frothing quantum foam to vast galaxy clusters, the journey to the beginning entwines the smallest scales with the grandest structures. Each new measurement chisels away at uncertainty, refining our portrait of cosmic evolution and challenging our preconceptions. As experiments push into previously uncharted territory, the boundaries between astrophysics, particle physics, and fundamental theory continue to blur. In pursuing answers to questions older than time itself, we not only uncover the forces that shaped everything we know but also spark fresh mysteries to fuel our collective curiosity. After all, humanity’s gaze toward the heavens is as much a voyage into our own beginnings as it is a quest to fathom the universe.